How can we help our pets adjust to us leaving the home again?

by Jon Kuiperij – Mar 22, 2022

by Jon Kuiperij – Mar 22, 2022

In Take 5, Sheridan’s thought leaders share their expert insight on a timely and topical issue. Learn from some of our innovative leaders and change agents as they reflect on questions that are top-of-mind for the Sheridan and broader community.

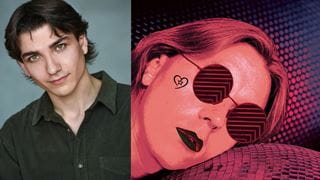

Many of us have spent the past two years eagerly waiting for the world to open up again, but there might be some in your home who aren’t thrilled to see you head back to the workplace or go away on vacation. In this installment of Take 5, Sheridan professor and Davis Campus resident veterinarian Dr. Roberta Veitch (pictured with her small Munsterlander pointer, Karma) discusses the separation anxiety that pets can experience when they’re apart from their owners, what pet owners can do to address it, and what the animal care industry is doing to help reduce pets’ anxiety, fear and stress.

Many of us have spent the past two years eagerly waiting for the world to open up again, but there might be some in your home who aren’t thrilled to see you head back to the workplace or go away on vacation. In this installment of Take 5, Sheridan professor and Davis Campus resident veterinarian Dr. Roberta Veitch (pictured with her small Munsterlander pointer, Karma) discusses the separation anxiety that pets can experience when they’re apart from their owners, what pet owners can do to address it, and what the animal care industry is doing to help reduce pets’ anxiety, fear and stress.

1. How common is separation anxiety in pets, and are there any health concerns associated with it?

It’s quite common, but to varying degrees. The main health worry is the really severe cases in which the pet might hurt themselves trying to get to their owner. For example, if they’re in a crate, they might hurt their nails or their nose trying to get out. I’ve also seen a dog jump through a window to get out to its owner, and intelligent birds like parrots might start picking their feathers and displaying other destructive behaviour.

Most often, however, our pets are just very anxious when we’re away. That generally makes it a quality-of-life issue more than anything.

2. Are any particular animals or breeds of animals more susceptible to separation anxiety? What about pets who were in homes before the COVID-19 pandemic and were once accustomed to being separated from their owners?

Not many animals form bonds with people in the way that cats and dogs do, and their vulnerability to separation anxiety can depend on their relationships with their caregivers. If they’re in a family that shares the feeding and the walking and other responsibilities, that love is spread around. If only one person feeds the dog and walks the dog and supplies the dog with things it likes or needs or wants, that person becomes the dog’s focus, so if that person is suddenly gone more, it becomes a problem.

Even pets who were in the home before the pandemic will have become used to different patterns and schedules. They don’t remember that two years ago, you used to leave for work every day, so they’re just as vulnerable as pets who haven’t had the experience of mom and dad regularly leaving the home.

“All (pets) want is to feel secure. When different things start happening and they have no clue why or what to expect next, they get anxious.”

– Sheridan professor and Davis Campus resident veterinarian Dr. Roberta Veitch

It also depends on the pet. Some people adapt well to change or even thrive on it, while some people are frightened by it, and it can be the same with pets. Some will adapt faster than others, but it could take a month to get back into a pattern that they feel secure in. All they want is to feel secure. When different things start happening and they have no clue why or what to expect next, they get anxious.

3. How can you tell if your pet is suffering from separation anxiety?

Mental illness is difficult to diagnose in animals because they can’t tell us what they’re thinking or how they’re feeling. But we certainly know that animals can have anxiety, and they express it in different ways. Cats usually express it by urinating in places where they usually don’t urinate, while dogs might not eat for a number of days.

When you start leaving your home more, it’s safe to assume there’s going to be a period of adjustment. If you live in an apartment, you might want to ask your neighbours if they heard whining or crying or barking while you were gone. You can also look around your home for evidence of house soiling or excessive drooling.

Another thing you can try is leaving your phone in a spot where your pet usually hangs out and record a video while you go for a five-minute walk without your pet. That’s probably the best way to know if your pet is upset when you aren’t there, unless your partner or roommate or children are home while you’re gone and can observe the pet’s behaviour for you.

4. How can you help your pet cope with you being out of the house more?

There are various nutraceuticals and amino-acid, protein-based foods and formulas that can help calm your animal during the adjustment period, but prevention is always your best bet.

Teach your pet that being alone can be a good thing by giving them a special treat or reward that they only get when you aren’t around. For example, whenever I leave the home, my dog gets a dental chew, which she thinks is really exciting. This helps them associate being apart with a high-value reward instead of associating being apart with horrible feelings and stress.

Also, don’t make coming and going a high-intensity event, because that can just heighten the anxiety. Just calmly get up, give your pet a treat, and leave. When you get back, ignore your pet for the first 10 minutes or so. You may also want to try changing up the routines you go through when you’re preparing to leave the house, because pets — dogs especially — recognize patterns really quickly. The minute the pattern starts, the anxiety can start as well.

5. Has the animal care industry made any recent changes or adaptations to how it handles animals?

Something that has recently emerged in the industry is the Fear Free movement, which aims to avoid or minimize the fear, anxiety and stress that pets experience as patients in our animal hospitals. Just like rewarding your pet when they’re about to spend time alone, it’s about helping pets make positive associations with unfamiliar situations to help decrease the stress.

By understanding that animals have anxiety and fears, we can understand that some of the bad things we might associate with animals are actually normal behaviours. For example, if a dog tries to bite you when you’re trimming his nails, it’s because he’s fearful and it’s the only thing he knows to do. In the past, animal care technicians might have held the dog down and clipped the nails, but that can make the anxiety much worse. Now, we can prepare the dog for that situation through 'Happy Visits' or 'Victory Visits' (social trips to the clinic that build positive emotional connections) and getting it used to having its paws handled in advance, or we can calm the dog with treats or sedatives.

Essentially, the Fear Free movement promotes dealing with animals in a more compassionate way, and it’s something that we emphasize to our students quite a bit. I would estimate that about 10% of animal clinics in southern Ontario are fully Fear Free, but most would have at least one or two employees who have been through that program and understand its benefits. In the next five years, I think we’ll see a lot of changes in how clinics operate to minimize fear, anxiety and stress in animals.

Dr. Roberta Veitch has been the resident veterinarian at Sheridan’s Davis Campus since 2009, overseeing the care and use of live animals that are owned by Sheridan for teaching purposes. In addition to teaching in Sheridan’s Animal Care and Veterinary Technician programs, Roberta also works part-time in a private small animal veterinary practice, helping her remain current with standards of practice, new diagnostic methods and treatment options. She holds degrees in Education and Biochemistry from the University of Toronto as well as a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the University of Guelph.

— This interview has been condensed for brevity and clarity. Header photo by Doug Hall.

Media Contact

Meagan Kashty

Manager, Communications and Public Relations